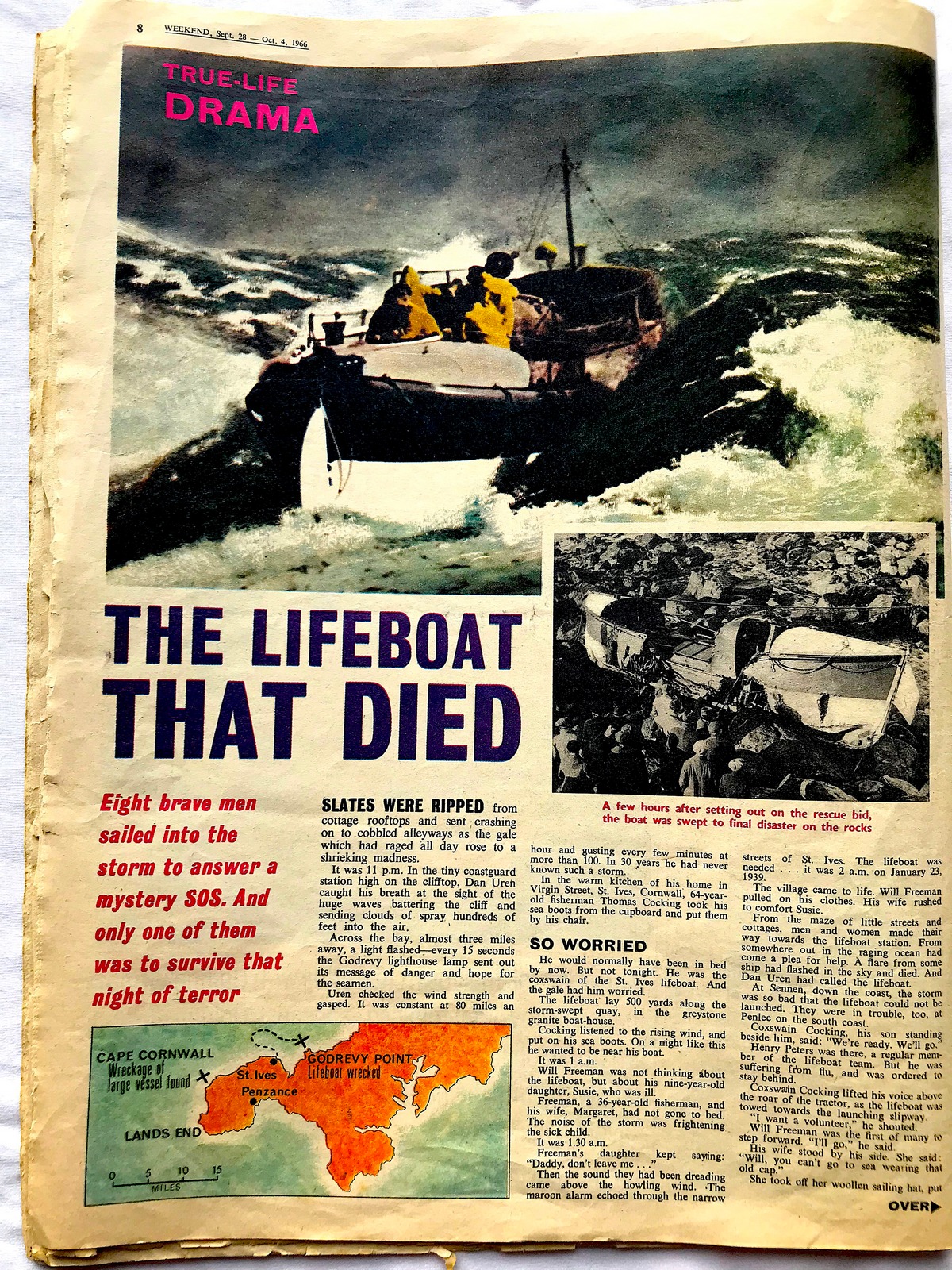

The wreckage of the John and Sarah Eliza Stych is examined. Photograph: Niki Brookes from archives at St Ives Museum

Today marks 81 years since the John and Sarah Eliza Stych lifeboat launched in a violent gale to the aid of an unknown vessel.

On the night of a vicious storm, with a wind speed of up to 100 miles an hour, distress signals were reported a mile out to sea shortly after midnight. So strong was the wind that it took more than 80 volunteer men and women to launch the lifeboat from St Ives Point at 3am.

Coxswain Thomas Cocking was in command of an eight-man crew, including volunteer Will Freeman, who took the place of a crew member who hadn’t heard the sound of the maroons such was the wind, to serve aboard a lifeboat for the very first time. St Ives had not replaced their lifeboat, which had been lost, and had Padstow’s on loan.

Such was the ferocity of the storm that the lifeboat had only travelled a mile or two before disaster struck. Despite coxswain Cocking’s best efforts, the gale took control and a huge wave capsized the lifeboat. She was able to self-right but when she re-appeared four of the crew, including the coxswain, had vanished. Two others were clinging onto rope grips on the side of the boat and managed to haul themselves back onboard.

With a crew of four they had no other choice than to turn back, but further tragedy was still to come. The gale had torn the sail to tatters and the propeller had been damaged, leaving the four remaining crew at the mercy of the sea. Exhausted, they managed to launch a red flare, which was seen from the town, but the horrendous conditions meant it was impossible for anyone to help. A huge wave capsized the lifeboat for a second time.

A contemporary newspaper report. Photograph: Niki Brookes from archives at the St Ives Museum

For a second time the lifeboat self-righted herself, but they had lost another man who had been swept overboard. The remaining three crew members were clinging as best they could to the battered lifeboat, as every attempt to make it back to the safety of the shore was thwarted by the storm.

A huge wave lifted the lifeboat and then slammed her down on the water, and as she capsized for a third time and self-righted once again, the lifeboat was thrown onto the rocks. This time it left sole survivor, Will Freeman, the man who was aboard a lifeboat for the first time.

When the storm subsided the remains of the vessel the lifeboat launched to, SS Wilton, was found washed up on the shore with no survivors from the 30-man crew. Will Freeman passed away on January 23, 1979, exactly 40 years to the day of that fateful launch.

Bronze medals were awarded to William Freeman and, posthumously, to Coxswain Thomas Cocking, Matthew Barber, William Barber, Richard Stevens, John Cocking, John Thomas, and Edgar Bassett.

Rob Cocking, whose great grandfather and great uncle lost their lives in the disaster, has been coxswain of St Ives’ lifeboat since 2015. He continued a long family tradition when he took on the role, following them, his father and brother.

Current St Ives Coxswain, Rob Cocking. Photograph: Jack Lowe for the RNLI

He said: “These men were local St Ives men. They went out in the most appalling weather conditions, regardless of what could happen and what the outcome would be. They went out to save the lives of others — and in doing so tragically and selflessly lost their own lives.

“Every one of those men should be remembered always for what they gave and sacrificed that night. I know that I will always remember what they gave, and I hope as time goes on, we always take time to remember the ultimate sacrifice.”

St Ives’ current lifeboat fleet includes the D class lifeboat and the Shannon, the latest class of all-weather lifeboat. The Shannon is the first modern all-weather lifeboat to be propelled by waterjets, instead of traditional propellers, making her the RNLI’s most agile and manoeuvrable all-weather lifeboat yet. It was designed entirely in-house, with the safety and welfare of crews a key priority in its development.

Alongside it, a new faster and safer launch and recovery system was designed to make sure the lifeboat can safely get back to shore, no matter what the conditions.

While the modern day lifeboats may be more sophisticated and technologically advanced than those used in the past, such as on that tragic night in 1939, the bravery and courage shown by RNLI volunteers then continues to be shown today.